Remembering Ho Chi Minh on his 135th birthday

As Vietnam marks the 135th anniversary of President Ho Chi Minh’s birth (May 19, 1890 – May 19, 2025), Ambassador Thong recalls Warbey, a British politician with a deep interest in Vietnam.

Born in 1903 in Hackney, London, William Warbey was a Labour MP from 1955 to 1966 - a period when Vietnam’s struggle drew growing international attention, particularly in Britain, one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and a signatory of the 1954 Geneva Accords on Indochina.

Warbey authored two books on Vietnam: Vietnam: The Truth (1965) and Ho Chi Minh and the Struggle for an Independent Vietnam (1972).

William Warbey, a British Labour MP, deeply engaged with Vietnam. Photo: Wiki

In May 1957, a delegation of British MPs visited Vietnam to monitor Geneva Accord implementation. Warbey recalled a sunny morning that month when President Ho Chi Minh hosted the British delegation for breakfast in the Presidential Palace garden.

There, President Ho Chi Minh explained Vietnam’s political strategy, emphasizing that reunification was not solely a military goal, but also required restoring economic ties and communication between North and South.

Warbey noted that prior to the meeting, they had learned of economic development plans in the North. In his May Day speech, Ho Chi Minh had already stressed strengthening the northern economy as a foundation for long-term national unification - aligned with the Geneva Accords.

Asked about necessary steps to implement the Accords, Ho Chi Minh reportedly surprised the group by calmly stating: “We can be patient. Time is on our side.” The first step, he said, was de facto reunification - reuniting families, restoring transport and communications, and rebuilding human and economic relationships between North and South.

At the time, in May 1957, the US had not deployed combat troops, the National Liberation Front had not yet been formed, and Laos and Cambodia were still peaceful. The world’s major powers were preoccupied elsewhere. But Warbey observed that Ho Chi Minh had already envisioned a strategy for eventual national liberation - one that required patience.

Warbey’s journal quoted Ho Chi Minh as saying: “Reunification of Vietnam through free elections is vital. North and South cannot live without each other. We are one people with one language, customs, and outlook. From both a human and economic perspective, reunification is essential.”

After visiting the North for three weeks, the British delegation traveled South. Warbey recalled that even Southern officials acknowledged the North was less corrupt and more committed to serving the people.

A master of revolution

During his second visit in January 1965, Warbey toured museums that chronicled the “Revolutionary Week” of August 19–25, 1945, across cities like Hanoi, Hai Phong, Vinh, Hue, and Da Lat. Crowds had rallied for “Freedom,” “Independence,” “Democracy,” and chanted “Nguyen Ai Quoc” and “Ho Chi Minh.” Warbey saw Ho Chi Minh, Truong Chinh, Pham Van Dong, and Vo Nguyen Giap as “masters of revolution,” who orchestrated an historic uprising to defeat colonialism.

He was particularly struck by Ho Chi Minh’s political foresight. Even in 1937, Ho predicted Japan’s imperial ambitions would crumble under pressure from China, the USSR, and the US. After the 1945 victory, Ho skillfully included nationalist elements in his government and declared independence before a massive crowd - estimated by French Commissioner Jean Sainteny to be in the hundreds of thousands.

Warbey noted that this revolutionary leadership enshrined values of freedom, democracy, and tolerance unmatched by many regimes then supported by world powers.

The second meeting and a missed opportunity for peace

In December 1964, Warbey joined peace efforts following high-level US-UK talks in Washington. He visited Vietnam with his wife in January 1965, seeking to meet Ho Chi Minh and Prime Minister Pham Van Dong to explore peaceful solutions.

On January 11, 1965, Warbey met President Ho Chi Minh - then 74 years old. He described him as warm, sharp-minded, charismatic, and delightfully humorous. Ho asked whether the British Labour Government was ready to propose a peace initiative independently of the U.S., expressing disappointment with the December talks.

In discussing the Geneva Accords, Ho Chi Minh reaffirmed Vietnam’s commitment to them as a foundation for peace - ideally through an internationally guaranteed agreement ensuring independence, neutrality, and non-interference.

Pham Van Dong later shared further details. Warbey found the Vietnamese proposals reasonable. He reported back to the UK, and by July 1965, Prime Minister Harold Wilson declared in Parliament: “The enemy of negotiation is the enemy of peace.” Warbey later lamented the lost opportunities for peace between 1965 and 1969.

Vietnam’s rebirth in 1945

After meeting Ho Chi Minh twice and studying Vietnam’s history, Warbey concluded: “Vietnam was reborn in 1945.”

He saw Ho Chi Minh as a strategic, practical leader. Born into poverty, Ho had received a strong education and deeply loved his people. He traveled abroad to learn revolutionary theory, then returned to lead his country.

Even in 1931, Ho Chi Minh understood the need for diversity in thinking. He believed the Party must sacrifice, consult the people, and practice transparency. Governance, he insisted, should be proven through daily deeds.

In 1964, Vietnam was on the verge of industrial growth. Ho advocated importing Western machinery, adapting it to national needs, and eventually producing it domestically with local resources.

According to Warbey, Ho Chi Minh was affectionately known as “Uncle Ho” because of his warmth, empathy, and deep love for the people. He believed in the people's wisdom and called for immediate general elections after the Declaration of Independence - to build legitimacy both domestically and internationally.

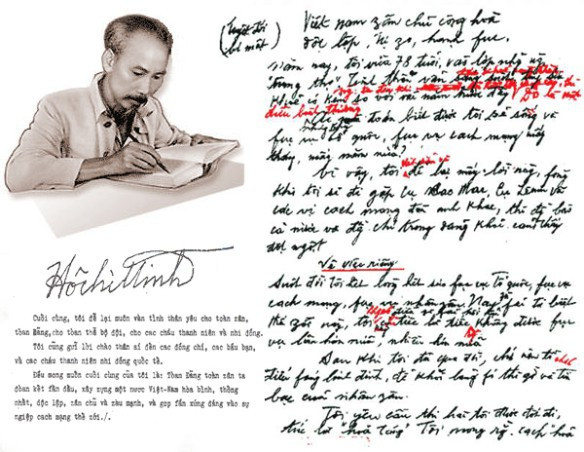

On May 10, 1969, Ho Chi Minh left behind a political testament urging unity, peace, independence, and prosperity for Vietnam - while supporting global revolutionary movements.

Warbey considered this testament a defining document for understanding both Vietnamese political history and Ho Chi Minh as a man - a light of Southeast Asia and the oppressed.

He cited praise from global leaders:

Prince Sihanouk called Ho Chi Minh “a symbol of the anti-colonial struggle for Asia, Africa, and Latin America.”

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi wrote: “His humility, humanity, and courage inspire all who cherish peace and freedom.”

The Guardian (UK), in a September 13, 1969 editorial, called him “one of the rare figures in history who truly reflected the aspirations of his people and devoted himself to the fight for the freedom of the oppressed.”

“These meetings happened 60–70 years ago, so archival materials are scarce,” said Ambassador Thong. “But in Volume 14 of the Complete Works of Ho Chi Minh (pages 451–454), there is an entry from January 11, 1965, confirming Ho Chi Minh’s meeting with William Warbey.”

Warbey asked: After all that Vietnam had endured, could friendship be restored between the Vietnamese people and those of Britain, the U.S., and Western Europe?

President Ho Chi Minh responded: “The friendship between the Vietnamese people and the people of Britain, the U.S., and Western Europe was never broken - so there is no need to restore it. The Vietnamese people are always ready to strengthen this friendship to resist warmongers and preserve peace.” (Ho Chi Minh Complete Works, Vol. 14, p. 454)

“His answer reflected both compassion and strategic clarity,” Ambassador Thong concluded. “He made a vital distinction between peace-loving people and those responsible for inflicting suffering on our nation.”

Thai An